The Hart Museum remains closed. Los Angeles County has approved a plan to transfer the William S. Hart Museum and Park from the County to the City of Santa Clarita.

Toothy Grins from the Past

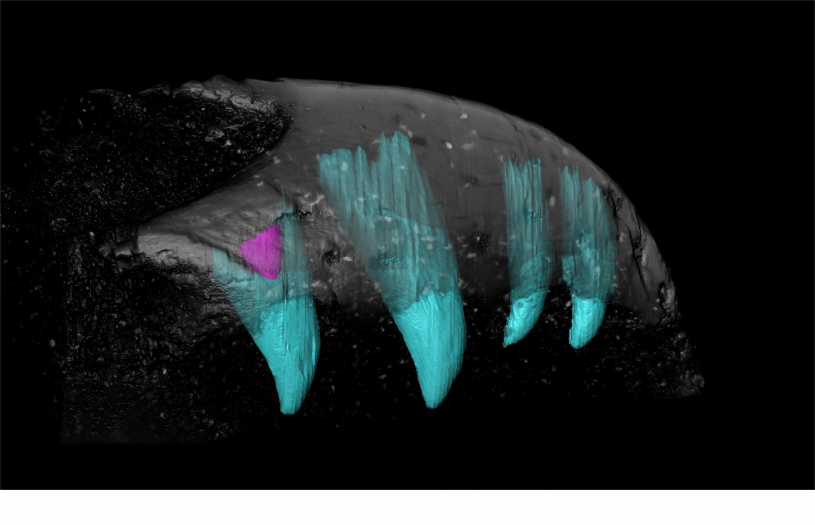

The first 3D reconstructions of extinct Cretaceous birds reveal a reptilian tooth replacement pattern

The birds flapping around in the Age of Dinosaurs had all sorts of different teeth in their mouths. Toothed birds went extinct along with their giant cousins, and modern dinosaurs –birds– are famously toothless.

Paleontologists have known that toothed birds lived in the Mesozoic since the discovery of the iconic Archaeopteryx in the 19th century. They also discovered that these birds replaced their teeth similar to some reptiles, but detailed examination of the tooth replacement process was limited.

In a new paper published in Scientific Reports, Graduate Student In-Residence at the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County’s Dinosaur Institute, Becky Wu, along with an international team of researchers from NHMLAC, used µCT imaging to get the first detailed look at the tooth replacement pattern of three newly discovered extinct Cretaceous birds from Brazil.

Wu and her colleagues suspected that to better understand the tooth replacement process and patterns, they would have to look inside the jaw. While previous studies have explored tooth replacement in ancient birds, they were limited primarily to what they could see on the outside. Wu and her colleagues applied microcomputed tomography to the fossils at the Molecular Imaging Center at the University of Southern California. Just like CT scans in hospitals or at dentists, this technology helped visualize the new forming bird teeth in the exquisitely preserved jawbones, helping Wu and her colleagues get closer to the root of tooth replacement patterns in these ancient birds.

“We kind of guessed,” Wu said. “We thought they probably had the replacement teeth, and were very happy to find them. This is the first time we were able to reconstruct the tooth replacement in a tooth row of birds, including those teeth that are still in their early stages.”

“The great preservation of the fossil and the high-resolution CT scan made this possible,” Wu continued, “We have records of tooth replacement in different developmental stages; this new data gives us a sneak peek of their tooth cycle. And since the specimens had preserved consecutive neighboring functional and replacement teeth, we can now visualize their tooth replacement pattern."

“We need three-dimentional data technologies like the synchrotron and CT scanning to understand the evolution and pattern of dental replacement and the mechanism of this complicated regeneration process,” says Wu.

The researchers discovered an alternating pattern of tooth replacement, similar to the pattern found in other dinosaurs and crocodilians. Even though the ancestors of crocodilians and dinosaurs split millions of years before either group appeared, crocodilians are currently the only living close-toothed relative to birds. The study’s findings imply that the genetic controls for tooth replacement survived that split.

“Crocodilians and birds stand on two ends of a diverse, connected family tree, yet the similarity of their tooth replacements suggests that the genetic mechanisms behind this process may have a deeper origin in that tree. We still need more data to fill our knowledge gaps, including data on crocodilians and dinosaurs’ ancestors and relatives and data on lineages closer to birds.”