The Hart Museum remains closed. Los Angeles County has approved a plan to transfer the William S. Hart Museum and Park from the County to the City of Santa Clarita.

A Ptango With Pterosaurs

How do the biggest wings the Earth has ever seen stack up to the flying reptiles of fantasy–dragons?

First Fridays 2023: Fandoms & Fantasy

This season, we focus on how nature and science influence the creation of our favorite imagined worlds. Read about how pterosaurs compare to dragons below, and check out the First Fridays page.

Dragons may cast a huge shadow over fantasy worlds, but pterosaurs were the biggest creatures to ever take wing on Earth.

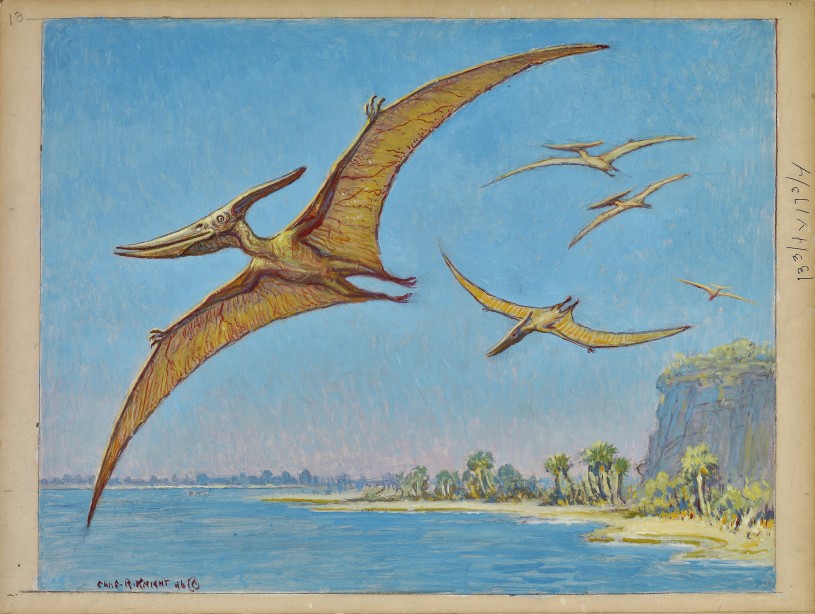

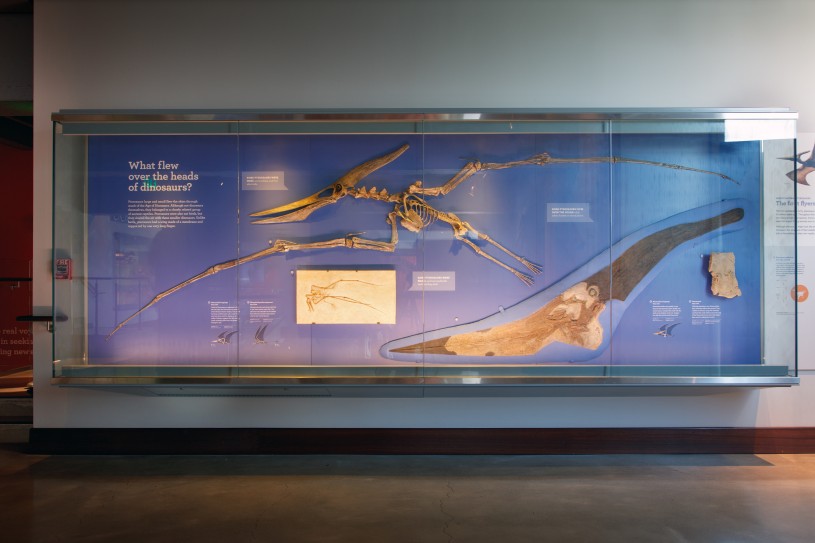

Pterosaurs were a diverse group of flying reptiles that reached similarly gargantuan sizes as they soared over the heads of dinosaurs from 228 to 66 million years ago.

Flight Craft

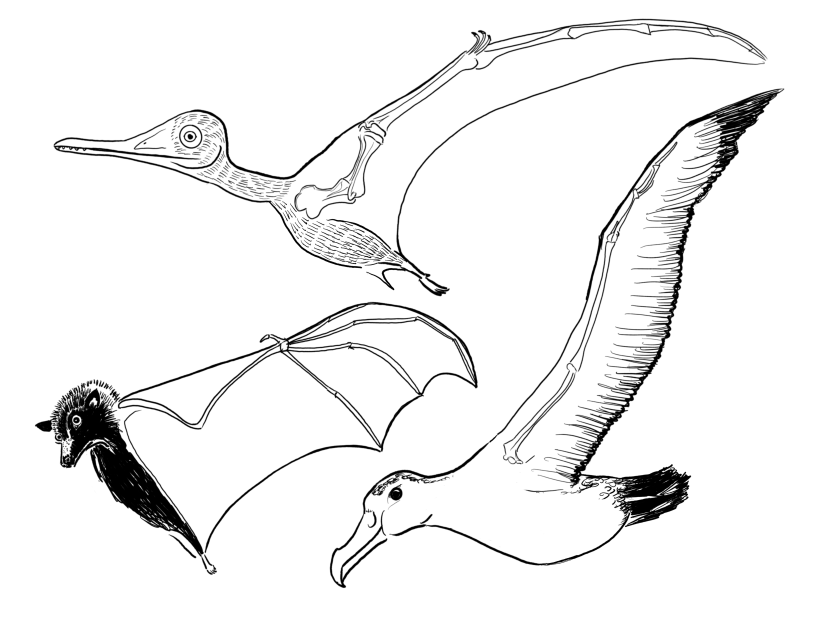

Author George R.R. Martin, the brains behind the beasts, has said that while most dragons have four legs, his dragons have two wings and two legs, which is more scientifically accurate. Putting aside the fire breathing, evolution agrees with him. On our planet, only insects have evolved wings on their backs; flying animals with backbones have adapted forelimbs into wings. After insects, pterosaurs were the first creatures that evolved powered flight and the vertebrates following their flight path used the same arm bones and a hundred million years of evolution to make three different wing types–with each type emphasizing different bones.

Of all the flying animals, pterosaurs got the closest to dragon-sized, but how closely do their wings align? They weren’t the closest wing to Game of Thrones dragons for Nate Smith, Curator of the Dinosaur Institute at the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County. “They've got a much bigger forearm and arm making up the wing whereas, in a pterosaur skeleton, most of the wing membrane and the wing is made up of that elongate fourth digit."

Pterosaurs get most of their wings from a super long 4th digit–let’s call it their wing finger. While the wing type of pterosaurs is a membrane–similar to that of bats and the dragons on screen. “The dragon is more kind of a bat-style wing from the look of it where you have pretty long arms and fingers,” says Smith.

Bats and birds spread out their wing structures, with bats moving their wings via three fingers and birds through bones attached to their feathers extending outwards. Birds’ many small bones fused with the wing surface make them the most active fliers we know about, and bats three-fingered wings help propel the flying mammals through the air, but only pterosaurs reached truly colossal size while maintaining flight. “I would say your Game of Thrones dragon wing, in terms of how it's constructed, the bones, and the proportions, is going to be most similar to a bat wing, less similar to a pterosaur wing, and very dissimilar to a bird wing,” says Smith.

With around 110 species, pterosaurs filled a number of roles, kind of like modern birds (which are dinosaurs) do today, spanning from the tiny to the tremendous. Some of the biggest pterosaurs are members of the Azhdarchidae family (from the word for the dragon-like azhdar of Persian mythology). While our understanding of pterosaurs is constantly evolving, and discoveries are popping up all the time (a new species from Argentina Thanatosdrakon amaru or the “Dragon of Death” being one recent contender), one pterosaur holds the crown.

Serpent God of the Skies

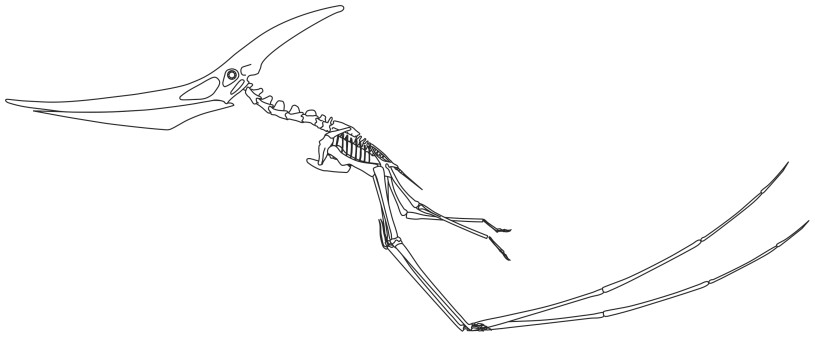

Aptly named for a feathered Aztec serpent god, Quetzalcoatlus would have cast a very big shadow over the Late Cretaceous, soaring overhead while T. rex still stalked the earth some 70 million years ago. There are currently two species of Quetzalcoatlus identified by paleontologists, both found in Texas, but Quetzalcoatlus northropi–the bigger species–is what we’re referring to here. It boasted a wingspan between 33 and 36 feet–as wide as a small airplane. Quetzalcoatlus had other notable features that were distinctly un-dragon.

Like many pterosaurs, Quetzalcoatlus had a crest on its head, fittingly regal for the king (or queen) of pterosaurs. It also had a long neck (11.5 feet) like a lot of depictions of dragons, but it ended in 10 feet of head composed of mostly beak–and no teeth. Pterosaurs generally had extremely large heads (and mouths) proportional to their body, leading NHM Dinosaur Institute Research Associate (and pterosaur expert), Dr. Michael Habib to call them “giant flying murder heads.”

Other features that helped Quetzalcoatlus get into the air would’ve been less apparent to their victims. Likely weighing around 500 pounds, parchment-thin hollow bones helped the giant pterosaur keep its weight down, and CT scans of other pterosaurs in the Azhdarchidae have revealed bicycle wheel-like bone structure that would have strengthened their hollow bones–letting them lift prey without breaking their necks. With proportions so wild, it can be hard to imagine how these animals might have moved.

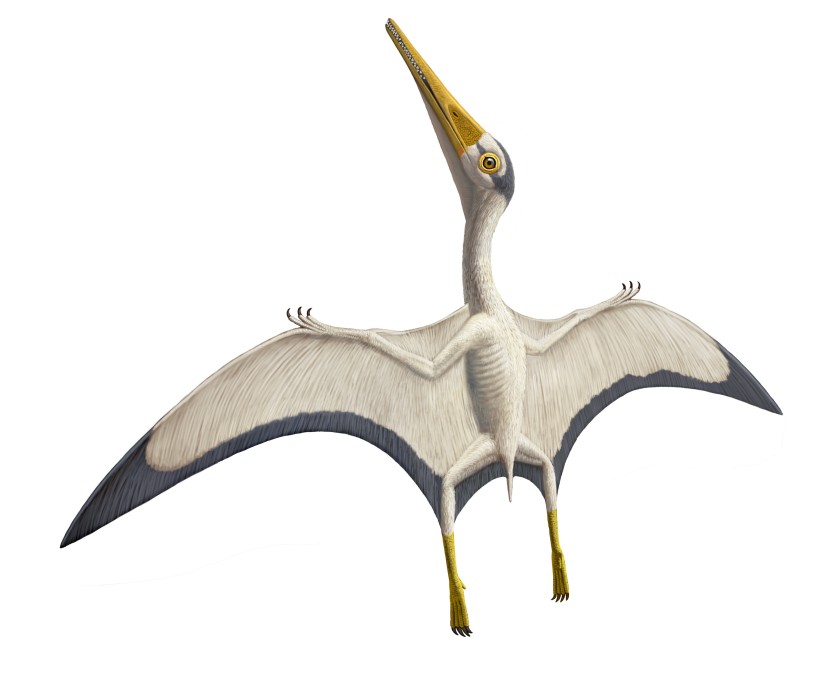

Image by Mark P. Witton1, Michael B. Habib used under the Creative Commons Attribution 2.5 Generic license.

Researchers have gone as far as creating mechanical ornithopters to see if the biggest pterosaurs could actually fly, and research by Habib suggests they could have taken trips as long as 10,000 miles. Recent studies have pointed to larger pterosaurs using their long wings/legs to pole vault into the air for take-off, an advantage that birds don’t have with only one set of legs, a structure that might help explain how pterosaurs were able to get so big. Much of their lives will likely remain a mystery–there is only so much scientists can reconstruct from fossils. The same ultra-light bones that let these giants take to the sky made them less likely to last in the fossil record, further complicating the quest to understand these creatures.

When the dragons started to get really big on Game of Thrones the creature designers behind the monsters struggled to imagine how they might get off the ground. So they looked to nature in a way. Specifically, they took apart a chicken from Trader Joe’s to see how the anatomy all fit together. Later, they looked to flying predators like eagles and found inspiration for how the dragons walked in bats. Combining traits from living animals helped make these fantastical creatures more believable, but extinct animals can go beyond the horizons of our imagination.

While even the mighty Quetzalcoatlus wouldn’t hold a candle to the fire-breathing ferocity of the dragons of Planetos (Drogon from Game of Thrones reaches the size of a Boeing 747), evolution produces something fundamentally stranger than human imagination and gets there in even weirder ways. How did the story of pterosaur flight begin? A recent study by Smith found that the tiny lagerpetids, including Dromomeron romeri—a tiny creature from the Late Triassic of Ghost Ranch, New Mexico, are the earliest known relatives to pterosaurs, and may have inched towards the edge of flight through sophisticated ears.