The Hart Museum remains closed. Los Angeles County has approved a plan to transfer the William S. Hart Museum and Park from the County to the City of Santa Clarita.

Hidden within what seems to be a muddy pile of dirt lies 45,000-year-old secrets. These little piles contain microfossils—bits of bone, plants, or bugs less than 1 centimeter in size. This debris is a tiny window into a world in which giant mammoths and mastodons once roamed.

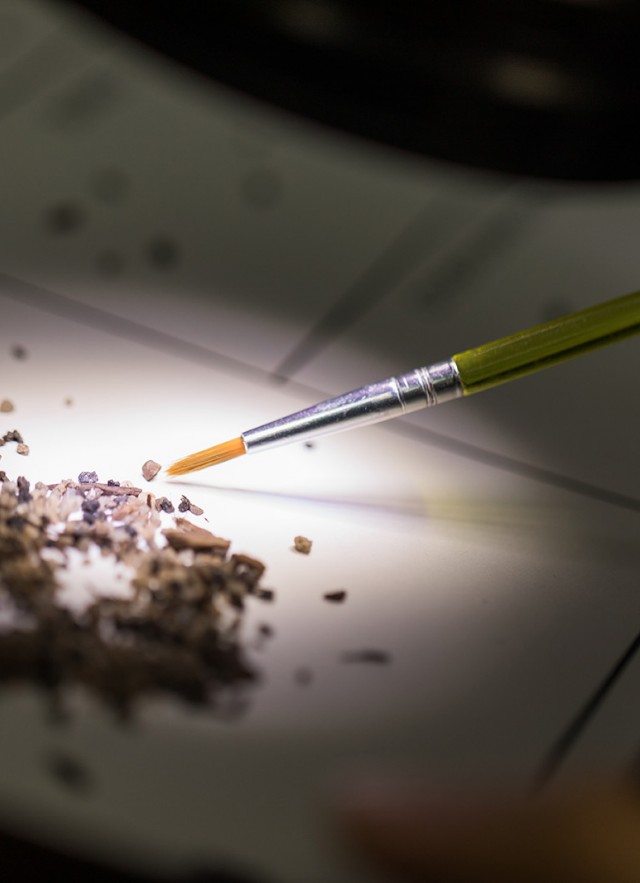

To investigate, researchers carefully sift through larger rocks and sediment. In one technique they swirl the mix of matrix into a large bucket of water. The heavier objects sink to the bottom, but the tiny fossils float. Like panning for gold, these precious pieces get skimmed off the top. Just one gram of sediment can contain anywhere from hundreds to thousands of pollen grains and phytoliths. Pollen grains are tough, which is why they preserve.

Phytoliths are tiny, microscopic crystals that form in plants when they're alive. And when the plant dies and decays, all those silica crystals get dumped into the soil, and then if the soil is preserved, you have a microscopic record of vegetation that’s just composed of these little silica crystals.

“The phytoliths and pollen really put a story together,” says La Brea Tar Pits Assistant Curator Reagan Dunn. “Those little fragments don’t look like much, but you put them under the microscope and you can get a lot of information out of them.”

Environmental Clues

One of the biggest debates about this era is why the Pleistocene extinction occurred at all—what happened to the mastodons, the ground sloths, and the dire wolves? Was it humans or climate change that drove these large mammals to extinction?

These phytoliths and pollen can help reconstruct the picture of a landscape, forests, and wetlands, of 50,000 years ago and reveal what ancient animals ate and even what the air was like. “We can get the atmospheric CO2 levels from them by looking at the anatomy of the stomata, the little pores on the leaf surfaces,” explains Dunn. By seeing how rapid warming events and glacial periods affected plant life (and, of course, the large mammals we love) we can understand the way future changes will impact the world as it is now.