The Hart Museum remains closed. Los Angeles County has approved a plan to transfer the William S. Hart Museum and Park from the County to the City of Santa Clarita.

Our Changing Planet

Whether through fossil digs, bug hunts, or ocean dives, NHMLAC is uniquely situated to gather, study, and share new knowledge about our changing environment.

There are no conversations more important to have than those that seek to understand how life exists, changes, thrives, or perishes on this planet. Climate change, the term used to encompass the evidence of Earth’s changing climates, is touching all of our lives and the wildlife that surrounds us. We know that human activities, particularly over the last 100 years, are turning up the planet’s thermostat—carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gasses are released into the atmosphere through the burning of fossil fuels (and other activities), trapping the sun’s heat. Such global warming means severe heatwaves and droughts, melting polar ice caps and glaciers, rising sea levels, changing ocean chemistry, more intense storms, and a dramatic impact on mass human migration and the ecosystems we rely on for our survival.

As the steward of vast collections documenting Earth’s history over millions of years, NHMLAC is uniquely situated to gather, study, and share new knowledge about our changing environment because these collections are time capsules of nature’s past. Every day at NHM and La Brea Tar Pits, our scientists are using the collections to research the past and foraging for data, with the help of curious Angelenos, about the biodiversity that surrounds us today. Here’s how:

IN RECORD TIME

Many of our fossils date back millions of years. By digging into our collections, we get a snapshot of how Earth transformed.

“Museum collections are essentially the only record that we have for the most part, going back through time,” said Dr. Nathan Smith, Curator of NHM’s Dinosaur Institute. The paleontological record provides important context. Smith will look at a fossil, for example, from the late Triassic during the dawning of the Age of Dinosaurs, and identify how warming led to a major mass extinction event that played out over hundreds of thousands of years.

“The rate at which species are going extinct now is just as high as it has been for some of the big five mass extinctions in the past. It’s not as if Earth hasn’t been warm at different intervals in the past, but it’s the rate at which we’re warming that’s problematic.”

While the bones of dinosaurs can tell us sweeping stories of the past, sometimes other fossils can yield just as enticing climate clues. Dr. Austin Hendy, NHM’s Assistant Curator of Invertebrate Paleontology, finds a pearl of wisdom in every oyster he sees.

“Just like a tree has tree rings, you can sample the calcium carbonate and all of these layers of the oyster shell and reconstruct environmental change during this lifespan.” A single shell can yield so much information: what seasons were like, how much it rained, what the temperature was, even how much food was available. This kind of information helps scientists recreate the environment of the past and learn what happens when a major upheaval occurs.

NO BONES ABOUT IT

Before smartphones and apps, scientists hand-collected specimens from the field and kept detailed notes of precisely where they were found, the surrounding conditions, and other data. Now, technology and crowdsourcing allows our scientists in our Urban Nature Research Center to observe and track wildlife biodiversity throughout L.A. County at an accelerated pace and larger scale. UNRC conducts BioBlitzes, one-day information-gathering surveys of insects, lizards, amphibians, and squirrels with the help of eager members of the public. Tracking how species move helps us understand the present moment.

In a recent study, Dr. Brian Brown, NHM’s Curator of Entomology, found that phorid flies are especially sensitive to temperatures. Like Goldilocks, the most diverse areas were in a sweet spot where it wasn’t too hot or too cold. This suggests that as climate change causes shifts in temperatures, insect biodiversity will change, too. And insects are key components of land ecosystems that provide essential services for humanity, including pollination, pest control, and medical drugs. “Our data show that temperature has a definite effect on phorid fly communities,” says Brown. “As urban areas become warmer, we expect changes that will alter the dynamics of these and other insect populations, which may also alter the ecosystem services they provide.”

Big initiatives like these are also a way to document the success of nonnative species, which arrived regularly into L.A. and can have harmful consequences on native wildlife. The suite of nonnative species that can establish is dependent on climate. And as the climate warms and there are fewer freezes, the types of species that get successfully established will change.

We’re also seeing these shifts in our seas today. Dr. Greg Pauly, NHM’s Curator of Herpetology, has documented that yellow-bellied sea snakes, typical of tropical waters, have been showing up on L.A.’s shores with more frequency in recent years (in the past five years, five have washed up on our beaches). The warming oceans might have lured the snake’s food sources north. Pauly thinks a pattern could be emerging, and that if it continues, “something remarkable is happening in our oceans and the species it supports.”

COLLECTING AS A FUTURIST

While bones and notes tells us a lot now, we don't know how future scientists will use our specimens. Some of our collections from 100 years ago are just pretty shells—no one thought to save the squishy parts, the soft tissues of snails and oysters. Other specimens were pickled in formalin, which preserves anatomy but destroys DNA. Fast forward a century, and modern technology allows us to recover DNA data from little bits of tissue left in those shells or unaffected by formalin. Therefore, old collections are allowing scientists to study decades-old specimens, even from extinct or threatened species.

So when we collect things now, we have to think of how future scientists might look at these collections and what technology they might have 100 or 200 years.

Dr. Allison Shultz, NHM’s Assistant Curator of Ornithology, says that’s why we keep studying and collecting. “If we don’t have physical specimens there’s no way we can study a lot of how animals are responding. We might be able to look at range shifts, but I can’t get DNA from a photograph and look at how the genome is evolving. So that's hugely important.”

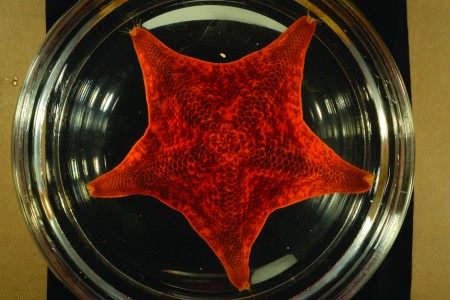

Another of the Museum’s major future-looking projects is NHM’s Diversity Initiative For the Southern California Ocean (DISCO), which is using a modern genetic technology, “environmental DNA” (or eDNA), to answer clues about local marine life. In the future, rather than collecting a bunch of new specimens every few years, we can take a cup of seawater and sequence all the unique strands of DNA in it. Since all animals and plants shed DNA, from that small cup of water we can get a glimpse of what lives in that area. This provides fast data in a rapidly changing environment.

The goal is to build a storehouse of specimens and information about what ocean biodiversity is like now, before more changes occur due to rising temperatures and rising seas—and hopefully to understand if we’re doing enough to save it. We are already making progress, and what we have to do is double down on that.