The Hart Museum remains closed. Los Angeles County has approved a plan to transfer the William S. Hart Museum and Park from the County to the City of Santa Clarita.

Meet Dr. Sophia Jones

Part of the thrill of taking care of history collections is that you’ll never know what wonders an unassuming box may contain.

Published February 7, 2024

By Katie McKissick

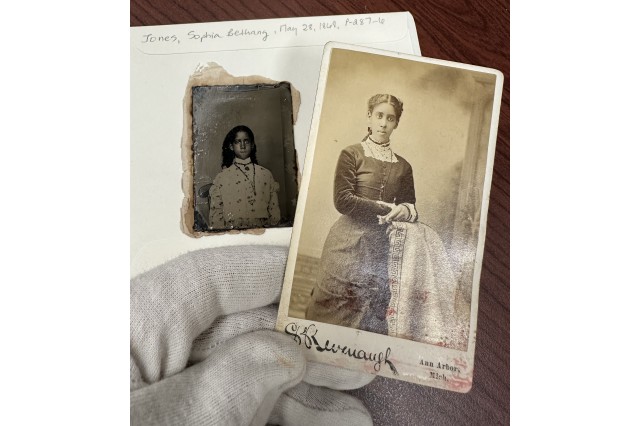

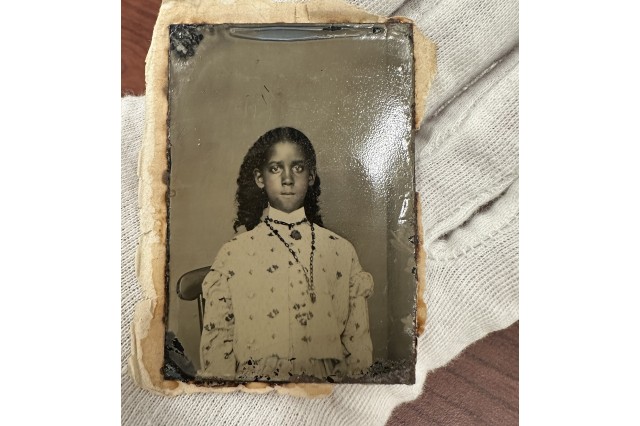

Part of the thrill of taking care of history collections is that you’ll never know what wonders an unassuming box may contain. When Senior Collections Manager Betty Uyeda was tending to the artifacts in the Seaver Center for Western History Research, she found a box labeled Sophia B. Jones Collection. She opened the card box and found a 150-year-old photo of an 11-year-old girl. The image is a tintype, a photograph developed onto a thin sheet of metal. Sometimes tintype portraits have trimmed corners for easy handling (as the metal is surprisingly sharp), but this one appears to have been glued into a paper scrapbook and later removed. On the back, the delicate paper has these handwritten notes in flawless cursive: “Taken May 28th, 1868” and “Aged 11 years and 11 days.” Below that, a different handwriting adds, “Sophia Bethany Jones.”

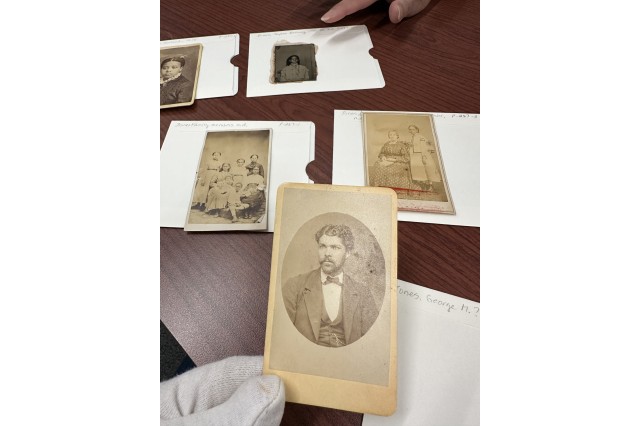

The collection also contains photos of an older Sophia, her sister Anna, her brother George, and a family portrait with seven people, including an infant. Several of the portraits were developed as cartes de visite — a “visiting card.” Approximately the size and weight of a playing card, they were shared and traded with friends in a similar fashion as business cards today. The back of cartes de visite include the name and location of the photographer, which was smart branding for portrait photographers back then, and very useful information for museum collections today. From their stamps we see the portraits were taken in Chatham, Ontario, Canada; and Oberlin, Ohio. We also know that Canadian-born Sophia and her sister Anna later moved to Monrovia, California—when they were in their late 60s—which is how they became part of the story of Southern California, and their portraits part of the collections at the museum.

The photos in this small collection provide a glimpse into the life of an African American family in the wake of Abolition and into the 1920s.

Seaver Center for Western History Research

Two photos of Sophia B. Jones taken 13 years apart—at age 11 in 1868 and age 24 in 1881.

A carte de visite of Sophia’s brother George, taken in Chatham, Ontario, Canada.

Seaver Center for Western History Research

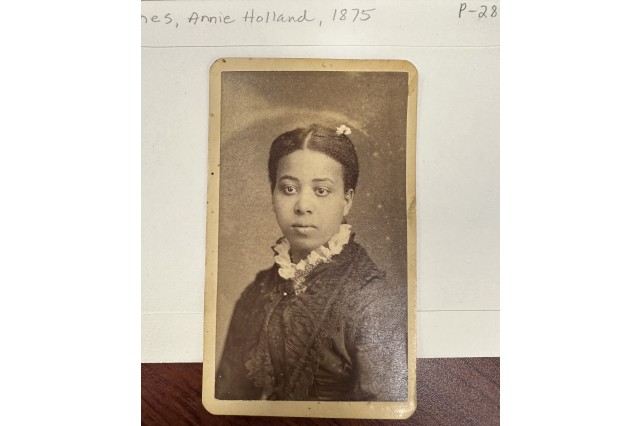

A photo taken in 1875 of Annie Holland Jones, Sophia’s sister.

Seaver Center for Western History Research

The image of 11-year-old Sophia Bethany Jones is a tintype, a photograph developed onto a thin sheet of metal.

1 of 1

Two photos of Sophia B. Jones taken 13 years apart—at age 11 in 1868 and age 24 in 1881.

Seaver Center for Western History Research

A carte de visite of Sophia’s brother George, taken in Chatham, Ontario, Canada.

A photo taken in 1875 of Annie Holland Jones, Sophia’s sister.

Seaver Center for Western History Research

The image of 11-year-old Sophia Bethany Jones is a tintype, a photograph developed onto a thin sheet of metal.

Seaver Center for Western History Research

In 1885, Sophia B. Jones became the first Black woman to graduate with a medical degree from the University of Michigan — where today both an auditorium and lectureship bear her name in honor of her achievements. She spent her entire medical career serving Black institutions, and went on to become the first Black faculty member at Spelman College, and founded their nursing program. Based on her 1913 scholarly article in The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, "Fifty Years of Public Negro Health," we learn that she was passionate about public health and shined a light on the social and economic barriers at work in African American communities a half century after the end of the Civil War, and how they affect infant mortality, infections, and other health outcomes.

An unanswered question is how Sophia, a pioneer in healthcare and academia, came to be in Monrovia with her sister Anna, who was a teacher and women’s rights activist, in their 60s. At the time Monrovia included a segregated, rural community of citrus orchards. Uyeda found Sophia in the 1920 census living with her sister at 1301 S. Shamrock Avenue, at a time that the community was established, as evidenced by the incorporation records of churches in the area.

As with many of the remarkable objects in the Seaver Center for Western History Research, every detail we uncover branches into more questions for historians to ponder. To delve deeper into the rich history of Los Angeles during Black History Month, visit NHM’s Becoming Los Angeles exhibit. Go back in time and ask your own questions about the objects that give us a glimpse into the lives of the many people who have called Southern California home, like Sophia B. Jones.

Article research was provided by Betty L. Uyeda, Senior Collections Manager in the Seaver Center for Western History Research