The Hart Museum remains closed. Los Angeles County has approved a plan to transfer the William S. Hart Museum and Park from the County to the City of Santa Clarita.

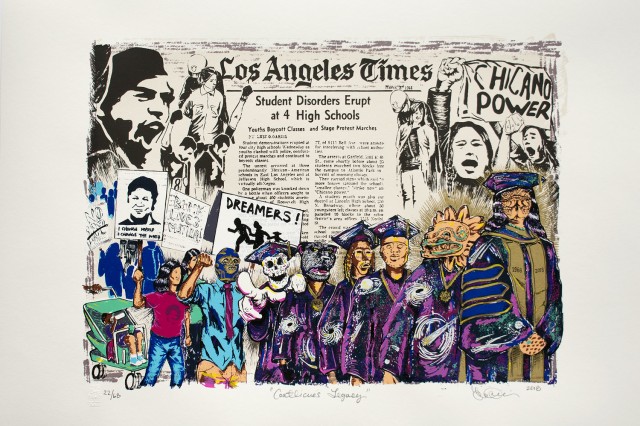

Margo’s Dresses of Resiliency

Originally costumes for the stage, these dresses cared for by the Museum are now artifacts that demonstrate the resilience against conspiracy amid country-wide hysteria.

María Marguerita Guadalupe Teresa Estela Bolado Castilla y O'Donnell, better known mononymously as Margo, was a dancer and actress during the classic Hollywood era.

Born in Mexico City in 1917, she and her family moved to New York in 1922, where she began her performing arts career as a dancer with her uncle Xavier Cugat’s Latin orchestra band. Beginning in 1934, Margo’s career trajectory was on the rise, with steady roles in Hollywood and Broadway. However, by the early 1950s, Margo’s credits changed from the leading lady in films to short features in T.V., which at the time did not hold the same status as film or stage. After her last role, Margo shifted her focus to philanthropy and arts education advocacy, sitting as a board member on several organizations and committees. An artist by trade, Margo’s career legacy of resilience and impact on Los Angeles lies in founding the cultural oasis at Lincoln Park—Plaza de la Raza.

The reasons for the change in career trajectory in the 1950s remain a bit hazy. Did Margo stop performing to raise children before becoming an arts philanthropist? Or was Margo’s career curtailed by a more extensive anti-communist campaign that swept Hollywood and the nation?

Setting the Scene

Margo’s career began when major changes were reshaping the world—Japan’s invasion of China led to border conflicts with the Soviet Union (USSR), Hitler was appointed Fuhrer in Germany, and civil unrest in Spain escalated into civil war. In each of these circumstances was growing support or disdain for Communism and Fascism, which would play key roles leading up to World War II that upon culmination would flare tensions between the United States and Russia into a conflict known as the Cold War.

While a radical change was sweeping across the world, the United States was in the thick of the Great Depression. In 1919 the Communist Party of the United States of America (CPUSA) formed and countless disenfranchised citizens turned to them in hopes of a brighter future. As a group forged for the people by the people, the party gained respect for pushing reform rather than revolution, civil rights, and economic justice.

Tessa Digital Collections of the Los Angeles Public Library

Crowd at Communist rally in 1935. Communist ideals have been around for centuries but our modern understanding grew out of the 19th-century people’s movement in Europe and spread further with the publication of The Communist Manifesto in 1848.

Tessa Digital Collections of the Los Angeles Public Library.

A 1930s rally at La Plaza in Downtown L.A. Communism questioned the capitalist system where the bourgeoisie (a minority class) owned the resources. The means of production employ wage labor from the proletariat: the large working class who sell their labor power to survive.

Washington Area Spark Flickr

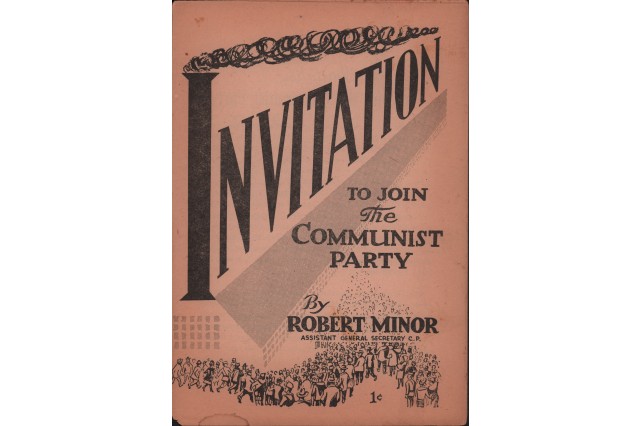

1943 CPUSA pamphlet. As a type of Socialism, Communism advocated for common ownership among all individuals and the absence of social classes. The demand and supply of goods would be regulated as necessary. The state would provide work and compensation according to a person’s capabilities, eliminating unfair wage gaps.

1 of 1

Crowd at Communist rally in 1935. Communist ideals have been around for centuries but our modern understanding grew out of the 19th-century people’s movement in Europe and spread further with the publication of The Communist Manifesto in 1848.

Tessa Digital Collections of the Los Angeles Public Library

A 1930s rally at La Plaza in Downtown L.A. Communism questioned the capitalist system where the bourgeoisie (a minority class) owned the resources. The means of production employ wage labor from the proletariat: the large working class who sell their labor power to survive.

Tessa Digital Collections of the Los Angeles Public Library.

1943 CPUSA pamphlet. As a type of Socialism, Communism advocated for common ownership among all individuals and the absence of social classes. The demand and supply of goods would be regulated as necessary. The state would provide work and compensation according to a person’s capabilities, eliminating unfair wage gaps.

Washington Area Spark Flickr

Under CPUSA, workers across the nation in different industries urged reform in the workplace through unionization. The entertainment industry was no different. After years of personal vendettas and industry-paralyzing strikes, the FDR administration passed the Wagner Act in 1935, granting workers the legal right to form unions. Its creator, New York Senator Robert Wagner, believed that increased wages backed by unionization would aid the US in economic recovery. Thus from writers to talent agents, each compartment in the motion picture industry required workers to register with a union. For select industries, unions would change the labor landscape across the US in years to come.

Entering Stage Right, the Blacklist

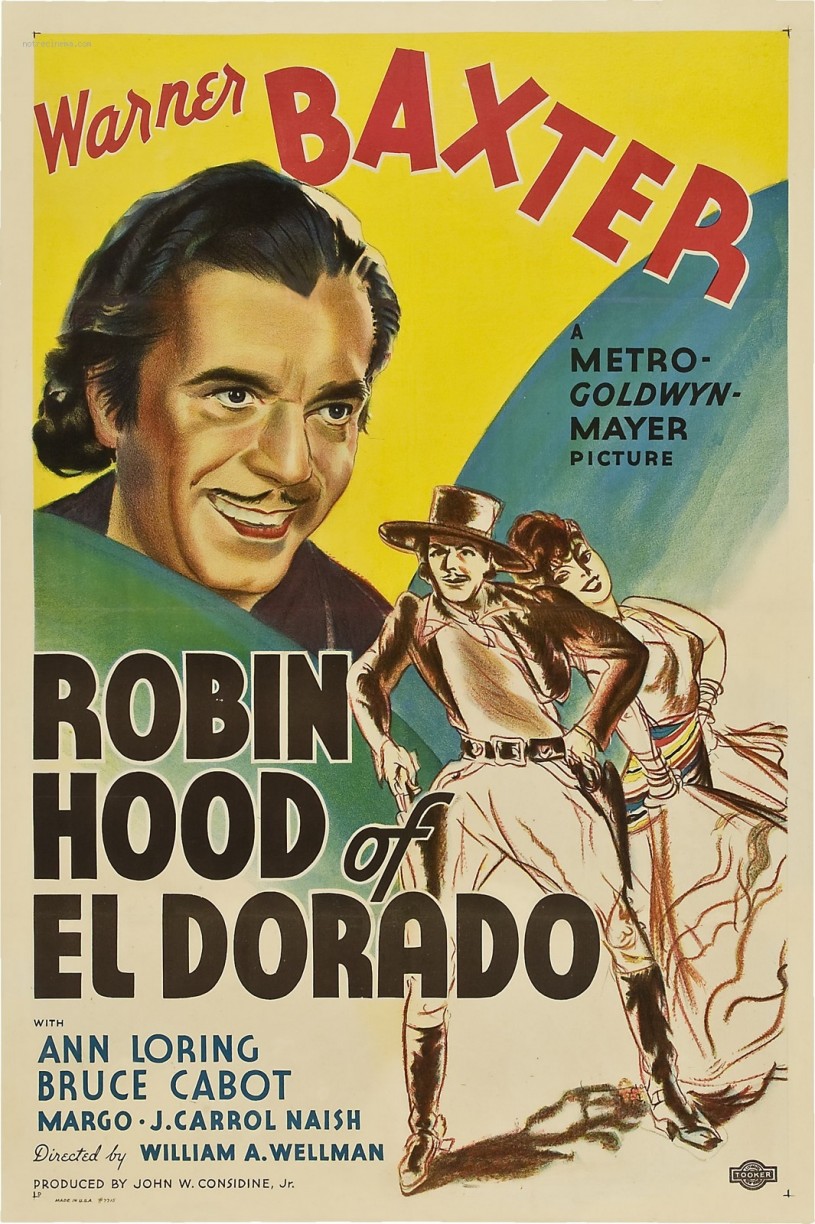

Some Hollywood films reflected the ideology of the times: ordinary small-town Americans would triumph over corruption, often characterized by politicians or big business. Margo starred in two films that would later be “blacklisted” in the coming decades for their “radical” outlooks– Robin Hood of El Dorado (1936) and Miracle on Main Street (1939). Industry creatives transcended their roles in the Popular Front to combat the growing rise of Fascism across Spain, Italy, and Germany. They participated in political action committees like the Hollywood Anti-Nazi League for the Defence of American Democracy. However, the end of WWII ushered in a dramatic plot twist in the political landscape that unraveled the livelihoods and careers of many Americans who had stood for civil and economic rights at home and abroad.

Unionization and outspoken individuals incited concern and opposition from conservatives who established the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) in 1938 to investigate alleged disloyalty and rebel activity. Their vague definition of “un-American” included Communists for their ideological ties to Russia. Despite allyship in World War II, the US sought to distance itself from Communist Russia and mobilized against public or “socialized” programs established under FDR’s New Deal. HUAC’s investigations shifted the tone of American politics, influencing the formation of the Hollywood Blacklist and other events such as the sabotage of the proposed public housing development in Chavez Ravine.

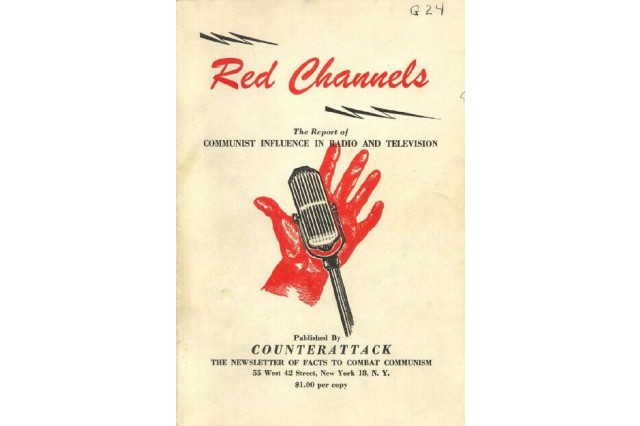

In 1947 HUAC subpoenaed artists for a nine-day hearing which gained national publicity for featuring Walt Disney, Ronald Reagan, and Lucille Ball, among many more. Some artists who named names took the hearings as an opportunity for revenge, rekindling old personal grudges from the years of union strikes. A group of dissenters known as the “Hollywood Ten” refused to engage, declaring the hearings a violation of their First Amendment rights, to which HUAC responded with imprisonment. In support of the Hollywood Ten, colleagues organized the Committee for the First Amendment, protesting the government’s targeting of the film industry. By 1950 lists of names and tensions grew - anti-communist publications like the Red Channels named Hollywood creatives with purported subversive activities. To appear patriotic, Hollywood industries blacklisted artists and denied them employment for years based on rumors and allegations of communist association.

Front cover of the Red Channels pamphlet, which lists the alleged subversive activities Margo participated in, such as supporting the Joint Anti-Fascist Refugee Committee, the Artists’ Front to Win the War, and the Committee for the First Amendment.

Tessa Digital Collections of the Los Angeles Public Library

An eager crowd waits to enter a House of Un-American Activities Committee hearing in 1953.

Tessa Collections of the Los Angeles Public Library

On March 28, 1953, spectators watched the ongoing HUAC hearing with camera crews pointed at the committee and witness stand.

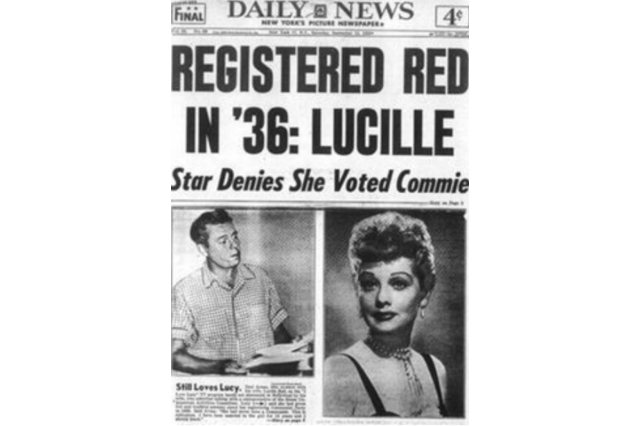

Lucille Ball makes headlines in the Daily News in 1953 for admitting that she registering as a Communist in 1936, but was never an active member of the party.

Tessa Collections of the Los Angeles Public Library

Pictured here are eight of the "Hollywood Ten" writers and directors who were convicted of contempt, along with three spouses of the writers/directors. Front, left to right: Edward Dmytryk; Mrs. Sadie Ornitz; Mrs. Albert Maltz; Mrs. Lester Cole; and Herbert Biberman. In rear: Alvah Bessie; King Lardner Jr.; Samuel Ornitz; Albert Maltz; Lester Cole; and Adrian Scott.

Tessa Digital Collections at the Los Angeles Public Library

Some members of the “Hollywood Ten” leaving for prison flanked by demonstrators showing their support for their freedom.

USC Fisher Museum of Art, Facebook

The Blacklist art piece and reflection garden was installed at the USC Fisher Museum of Art in 1999 to serve as a reminder of the countless people who sustained blacklisting and intimidation during the McCarthy Era of the 1940s and 1950s.

1 of 1

Front cover of the Red Channels pamphlet, which lists the alleged subversive activities Margo participated in, such as supporting the Joint Anti-Fascist Refugee Committee, the Artists’ Front to Win the War, and the Committee for the First Amendment.

An eager crowd waits to enter a House of Un-American Activities Committee hearing in 1953.

Tessa Digital Collections of the Los Angeles Public Library

On March 28, 1953, spectators watched the ongoing HUAC hearing with camera crews pointed at the committee and witness stand.

Tessa Collections of the Los Angeles Public Library

Walt Disney was called to testify at HUAC hearing in 1947.

thekinolibrary, YouTube

Lucille Ball makes headlines in the Daily News in 1953 for admitting that she registering as a Communist in 1936, but was never an active member of the party.

Pictured here are eight of the "Hollywood Ten" writers and directors who were convicted of contempt, along with three spouses of the writers/directors. Front, left to right: Edward Dmytryk; Mrs. Sadie Ornitz; Mrs. Albert Maltz; Mrs. Lester Cole; and Herbert Biberman. In rear: Alvah Bessie; King Lardner Jr.; Samuel Ornitz; Albert Maltz; Lester Cole; and Adrian Scott.

Tessa Collections of the Los Angeles Public Library

Some members of the “Hollywood Ten” leaving for prison flanked by demonstrators showing their support for their freedom.

Tessa Digital Collections at the Los Angeles Public Library

The Blacklist art piece and reflection garden was installed at the USC Fisher Museum of Art in 1999 to serve as a reminder of the countless people who sustained blacklisting and intimidation during the McCarthy Era of the 1940s and 1950s.

USC Fisher Museum of Art, Facebook

The Scarlet Mark of Communism

The Hollywood Blacklist forced creatives to flee, hide, or adapt. Margo and her husband Eddie Albert were never members of the CPUSA, but their careers were challenged after their names appeared in the Red Channels. While Eddie’s career seems to have survived, Margo only found inconsistent roles on television. Together they adapted by recording independent music albums and performing at small venues, but details about this time in their lives are limited. Several of Margo’s performance costumes, now part of the Museum’s collection, are believed to have been worn at this challenging time for her and those listed in the Red Channels.

The list of “subversive” activities attached to Margo’s name in the Red Channels ironically illustrated the values she held dear, such as garment worker’s rights and dignity in the workplace. The Red Channels stated that Margo spoke at a garment rally for the American Labor Party in 1945, clearly demonstrating that she was an advocate for the makers of her beautiful costumes. It is no wonder that Margo kept a collection of costumes from her career, and in essence, cemented her respect and attachment to the costume makers who worked alongside her.

The small details in the construction of Margo’s dresses, now in the Museum’s collection, provides us with clues that they were specifically used as costumes. Pictured below is a predominantly orange dress with blue accents and metallic gold paint strokes, which creates a filigree effect. All around this dress are exaggeratedly large pleats (not sewn down to the waist), which would have moved in both directions when spinning, emphasizing the function as a dance costume.

The other two dresses in the collection are nearly identical, except for color. A “Brooks Costume Company'' label is stitched along the boning of the unembellished aqua and cream-colored dresses. Their simple satin exteriors seem formal, but the lack of a lining exposes their construction which, in addition to the tags, indicates they were worn as costumes. Keeping the interior construction helps costumers make quick alterations and repairs as necessary during production. It was common to have on-hand tailors present throughout production to help mend and alter costumes– which likely heightened Margo’s opportunities to commune, empathize with their work, and the plight for union recognition.

Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County History Department

This satin dress, in a vibrant aqua color, was made by the Brook's Costume Company.

Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County History Department

The interior structure of this dress was left unlined which provides clues that this dress was a costume. The exposed interior allowed for ease of fitting and repair to costumers on set. The label indicated it was made by the Brooks Costume Company in New York.

Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County History Department

This unembellished cream-colored dress is identical in style to the aqua dress in the collection, also fabricated by the Brooks Costume Company in New York.

Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County History Department

This cream-colored satin dress was also fabricated by the Brooks Costume Company, as indicated on the label on the left.

Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County History Department

Petticoats would have been worn separately underneath some women’s dresses and skirts to create volume. Many layers of fabric were found in almost every dress, which helped performers quickly change in and out of costumes during a live show.

Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County History Department

Many pink, orange, and red layers under the skirt of this dress create volume without the need to wear a separate petticoat.

Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County History Department

Floor-length rayon-crepe dance costume with satin lining and felt appliques. Worn in the 1940s or 50s.

Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County History Department

A hefty two-piece costume made of velvet skirt and bodice and embellished with metal trim and tassels.

Diana Sanchez

Diana Sanchez

Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County History Department

Two of Margo's capes made with layers of small fabric pieces.

Diana Sanchez

The Marion Write Inc. label was sewn into the dress, which was a New York costuming company.

Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County History Department

An up-close look at the many layers of fabric on the Marion Wright costume.

1 of 1

This satin dress, in a vibrant aqua color, was made by the Brook's Costume Company.

Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County History Department

The interior structure of this dress was left unlined which provides clues that this dress was a costume. The exposed interior allowed for ease of fitting and repair to costumers on set. The label indicated it was made by the Brooks Costume Company in New York.

Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County History Department

This unembellished cream-colored dress is identical in style to the aqua dress in the collection, also fabricated by the Brooks Costume Company in New York.

Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County History Department

This cream-colored satin dress was also fabricated by the Brooks Costume Company, as indicated on the label on the left.

Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County History Department

Petticoats would have been worn separately underneath some women’s dresses and skirts to create volume. Many layers of fabric were found in almost every dress, which helped performers quickly change in and out of costumes during a live show.

Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County History Department

Many pink, orange, and red layers under the skirt of this dress create volume without the need to wear a separate petticoat.

Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County History Department

Floor-length rayon-crepe dance costume with satin lining and felt appliques. Worn in the 1940s or 50s.

Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County History Department

A hefty two-piece costume made of velvet skirt and bodice and embellished with metal trim and tassels.

Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County History Department

Diana Sanchez

Diana Sanchez

Two of Margo's capes made with layers of small fabric pieces.

Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County History Department

The Marion Write Inc. label was sewn into the dress, which was a New York costuming company.

Diana Sanchez

An up-close look at the many layers of fabric on the Marion Wright costume.

Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County History Department

Margo Adapts and Advocates

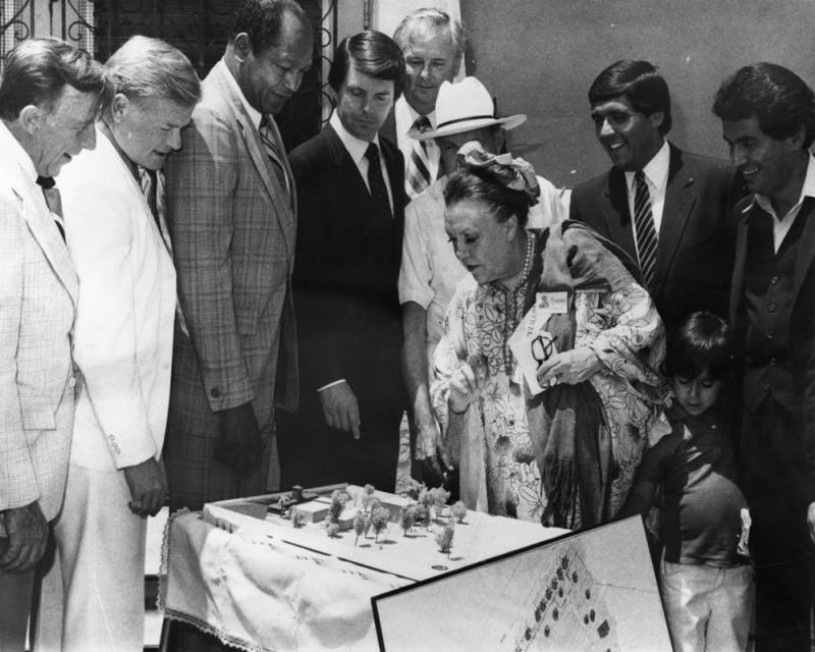

Margo’s political advocacy and love of the arts culminated with her actions to found Plaza de la Raza Cultural Center for the Arts & Education. Plaza de la Raza (which translates to “place of the people”) is located in Lincoln Park, which was originally named East Los Angeles Park, and contains a boathouse constructed in 1912. The boathouse was neglected for sixty years, and in the 1970s the City of L.A. ordered the park closed and the boathouse demolished. Margo stepped in and became active in the neighborhood movement to prevent demolition and instead moved to restore the building as an arts and cultural center. Together with other prominent labor and business leaders, they gained non-profit recognition and offered an array of arts programming, hoping to bridge the worlds of East and West L.A.

Throughout the 1970s, Margo served as artistic director and chairwoman of Plaza’s board, occasionally teaching drama classes designed for Latinos who did not have access to arts education and training. Inspired by the Federico Garcia Lorca quote, Margo believed in giving back to her cultural community: “The poem, the song, the picture, is only water drawn from the well of the people, and it should be given back to them in a cup of beauty so that they may drink - and in drinking understand themselves.” Over time Margo would be affectionately called la madrina (the godmother) of the Plaza, which would become a prominent educational and cultural center in L.A.

Lingering Red Channels

The Hollywood Blacklist began to break by 1960, yet the question and fear of communist association lingered in the political and social atmosphere. In 1980, Margo became subject to an FBI investigation after being nominated by President Jimmy Carter to the National Council on the Arts. Records indicate that the FBI questioned Margo’s membership in subversive “foreign or domestic organizations,” including the CPUSA, and interviewed friends who had been subject to HUAC’s accusations like Vincent Price, Eva Gabor, and Lucille Ball. In a 1998 biography of her father, Victoria Price reveals that Margo and the Price family were very close, calling Margo and Eddie “auntie” and “uncle.” Price revealed that some artists affected by the blacklist, like her father, often struggled to speak about that time and opted to shrug off questions. Perhaps out of fear of political retribution, Margo and her friends shared nothing but favorable information with the FBI.

One detail in the FBI record blurs the reasons for Margo’s career shift. She reported taking a sabbatical from 1957 to 1969 to raise her children Eddie Albert Jr and Maria Albert Zucht; however, Margo continued to act until 1965. Why then did she redact these roles from her story to the FBI? We may never know for sure, but upon reflection, Eddie Jr described his parents’ situation as tough because money was sometimes scarce. Perhaps the roles Margo took after 1947 were inconsequential gigs to help make ends meet. Perhaps the blacklisting branded her unemployable, and this challenge was something Margo preferred not to report on. More than thirty years after the trials, it seems that creatives were still walking on eggshells.

Margo went on to serve for the National Council on the Arts until her untimely death from brain cancer in 1985. Her life was celebrated with a memorial service at Plaza de la Raza that was attended by more than three hundred friends, relatives, and admirers. The Plaza’s students danced and performed between eulogies by chairpeople of leading cultural groups and politicians like Tom Bradley. Bradley described Margo as an “indomitable spirit” that “without her, this cultural center would not have happened.” Today, Plaza de la Raza is a gem in the eastside of town that fosters cultural enrichment, preserving and immortalizing Margo’s vision: to bridge the geographic, social, artistic, and cultural boundaries of L.A. and beyond.

Plaza de la Raza, Facebook

Since 1970, Plaza de la Raza has provided affordable arts education in the Eastside communities of Los Angeles.

Plaza de la Raza, Instagram

Plaza de la Raza continues to provide an array of intergenerational cultural experiences and affordable arts education programs.

1 of 1

Since 1970, Plaza de la Raza has provided affordable arts education in the Eastside communities of Los Angeles.

Plaza de la Raza, Facebook

Plaza de la Raza continues to provide an array of intergenerational cultural experiences and affordable arts education programs.

Plaza de la Raza, Instagram

A Folklorico dancer shows off her incredible gown at Plaza de la Raza.

Plaza de la Raza, Instagram

Plaza de la Raza hosts an annual Annual Día de los Muertos Celebration.

Plaza de la Raza, Instagram

Whether you look at her costume collection or visit Plaza de la Raza, Margo’s legacy demonstrates her resilience and how she used art as a way to connect with those in her community. Storing costumes until her death, it is evident that Margo appreciated them for their design, construction, and presumably memories. Now artifacts in the Museum’s collection, her costumes give us a glimpse into two facets of her life: her respect for tailors in the entertainment industry and her drive to work as a performer amidst the Hollywood Blacklist. Throughout her life, she valued truth and people’s right to live a life of freedom and dignity. When the blacklisting reduced her work opportunities, she paved new roads for herself before advocating for the arts. As founder of Plaza de la Raza, she left behind a legacy of community-building and cultural appreciation that has touched the lives of thousands of visitors and students each year. Margo’s story teaches us that valuing truth, empathy, and understanding can positively transform our lives and those around us, even in unprecedented moments of uncertainty.

A Note From Author, Diana Sanchez, Museum Educator

Margo’s story struck several chords within me. As an East L.A. native who attended arts programs at Plaza de la Raza and has a background in costuming for theatre, I had a unique perspective to view Margo’s costume collection. Her story also allowed me to see parallels to a time of unprecedented uncertainty.

Thanks to the History Collection Managers Beth Werling and Brent Riggs, I assisted in handling and documenting Margo's costumes– which brought Margo from being an abstract concept to a real-life person. It was surreal to make close observations and understand that each costume was made according to her dimensions– this detailed work challenged our initial plan to place them on a dress form. Each detail, from leotards attached to skirts to small hook and eye fasteners, were like puzzle pieces that at times prompted more questions than answers about form and function.

Moreover, Margo’s story and its connection to the Hollywood Blacklist seemed uniquely important to share for its message and impact. As a Latina and person of color, learning about my cultural history from textbooks or educational institutions is a rare but extraordinary opportunity. Including stories of historically excluded communities into school curriculum is empowering and necessary so that people of color like myself see themselves represented in history and carry the torch of change and progress. It is important to reflect on our collective history and learn from the people and circumstances that founded critical social movements that fundamentally changed society. Many do not realize that these movements were born from issues we still face today. Social security, unemployment insurance, and reforestation projects, to name a few, were vehemently supported by Socialism and Communism. While many of these rights must be updated to reflect today’s needs, the pandemic’s strain has unearthed this reality just as the Great Depression urged individuals to fight for these rights. These unprecedented times may be dire, but there is hope when we understand and reclaim our history and listen to historically excluded voices.