The Hart Museum remains closed. Los Angeles County has approved a plan to transfer the William S. Hart Museum and Park from the County to the City of Santa Clarita.

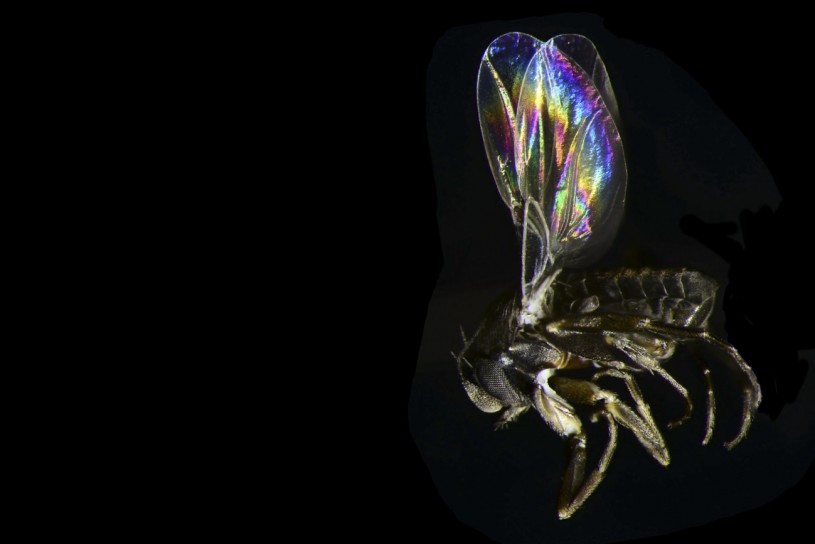

As you well know, we are fly obsessed here at BioSCAN. Particularly, we are phorid obsessed. I am particularly obsessed with the macabre species Conicera tibialis, commonly known as the coffin fly. Perhaps it's the shadowy lighting as I view them under the microscope, but these flies, with their dark velvety bodies and (almost sinister looking) conical antennae (males only, females have round antennae), appeal to me tremendously.

A number of phorid species are known to colonize humans remains, but C. tibialis seems the most determined. Adult females of this species are known to dig down through over two meters of dirt and enter coffins to lay their eggs. To complete an equivalent journey, a human being would have to dig two miles down — in perspective the feat seems all the more remarkable! Once the females reach the corpse they lay their eggs on, or near, the cadaver. The maggots hatch and feed on the decaying tissue — they are known to prefer lean tissue (while other taxa, such as some species of beetles, prefer adipose tissue). Yes, even corpse eaters can be picky! C. tibialis is known to be able to cycle multiple generations without surfacing (what they are doing below ground, the living can only imagine!). When the flies do surface, they do so by crawling the reverse path of their ancestors: back up through many feet of dirt. Charles Colyer, in a paper from 1954, conveyed the observations of his friend Mr. R.L. Coe that were some of the first key insights into the life history of this species. In May of that year, Mr. Coe observed a number of C. tibialis running about a patch of his garden, where 18 months before he had buried his deceased dog. As Mr. Coe observed more closely, he realized that all the running about was actually a mating frenzy — complete with pairs frolicking in coitu! On Colyer's request, Coe dug down to the corpse of his former pet, observing phorids at every depth along the way. The flies were all traveling toward the surface, in a mass exodus from the grave — hoping to join the mating party so that they might return to this, or another, grave and lay eggs of their own. Alas, Mr. Coe reported that by June 16 the phorids could no longer be found in their mating frenzy in his garden — where for weeks they had been seen "running over the ground in sunshine, and congregating under loose clods of earth in inclement weather".

C. tibialis is known not only to dig to astounding depths for corpses, but to wait unbelievably long periods of time to colonize. Corpses are typically utilized over a year after burial, and a paper by Martin-Vega et al. (2011) revealed a case where the species was found breeding on human remains 18 years postmortem. Phorid species are some of the key insects used in the field of forensic entomology — a branch of forensics utilizing insect life cycles to help approximate the age of a corpse. A story detailing the occurrence of C. tibialis in California was recounted by Father Thomas Borgmeier (1969), one of the "fathers" of phoridology. He was sent specimens of the fly that were collected in a mausoleum in Colma. A family had constructed an above-ground resting place for their deceased in 1962, and in 1965 noticed large numbers of the flies both in the mausoleum and around the cemetery. The family made the decision to open the four crypts. All four crypt interiors were dry and filled completely with C. tibialis and spiders. I bet the phorids were happy they had such easy colonization - no digging required! The take home message of this macabre tale should not be one of disgust. Although the details may be gruesome, insects that colonize corpses are performing the necessary breakdown of organic material that must occur postmortem. Only by this breakdown — by insects, fungi, and bacteria — can bodies be released to reenter the circle of life. Consumers of carrion are beneficial, performing an invaluable service to us below the surface. BioSCAN Principal Investigator Brian Brown likes to say that being food for C. tibialis is one way we can all contribute to the well being of phorids. I hope you might be as delighted by this fly as I am after reading the amazing life history and marveling at the amazing photos taken by our star photographer Kelsey Bailey, who expertly capture the dark, sleek aesthetic of this species on film (well ... digitally [did I just date myself?]). When I handed Kelsey a vial with several dried specimens, I told her I wanted creative photos to visually express the morbid life history of these flies. As you can see, she did not disappoint. I particularly enjoy the photograph at the top of the post — Kelsey beautifully mounted the specimen on the head of an insect pin — a glittery orb I wish appeared more often in entomological photos. I also like the film noir feel of the "portrait" she took of this species. Yes, I really like this fly. Perhaps my love for C. tibialis is so deep (two meters, to be exact) because I know they will be with me not just in life, but for up to 18 years past my death. VITA INCERTA, MORS CERTISSIMA.