The Hart Museum remains closed. Los Angeles County has approved a plan to transfer the William S. Hart Museum and Park from the County to the City of Santa Clarita.

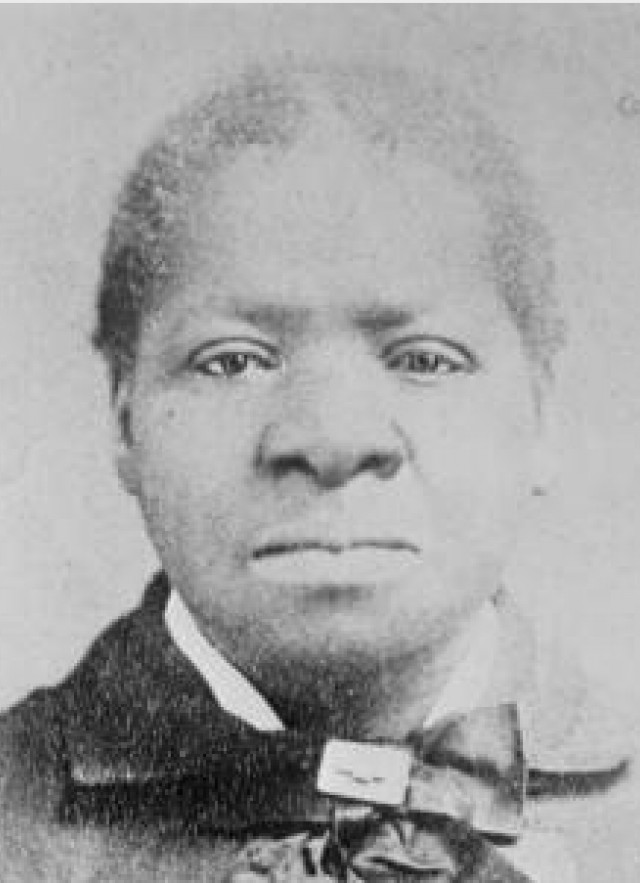

Biddy Mason: Her Stand for Freedom

A formerly enslaved woman who fought her way to freedom and built a legacy that puts the “angel” in Los Angeles

Biddy Mason’s life story reads like great fiction: a terrible struggle, a fight for justice, adventure, and then remarkable success. It all started with young love. Charles Owens, a young free black man, fell for Mason’s daughter Ellen. It was a time when slave-owning whites who migrated to California retained “ownership” over enslaved Black people through indentured servitude. When, in 1855, Mason’s slavemaster decided to move her and her children along with his family to Texas, where there was no such thing as free people, Owens took action. Enlisting his father in the effort, Owens rallied the local enforcement, along with a posse of vaqueros (cowboys), who together insisted that Mason and her people had a right to remain free and in California.

That is how Biddy Mason came to petition a California judge to free herself and her children. Mason knew the stakes. She’d been born into Mississippi’s plantation system and feared the tortures of slavery and reprisals her children would face if they were taken to Texas. As a woman of color, she was not allowed to speak in court. But even in a time of pervasive injustice, the law broke her way. While the nation was divided, the judge said the law of California was clear: “Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, unless for the punishment of crimes, shall ever be tolerated in this State."

DELIVERING A LOS ANGELES LEGACY

After her emancipation, Mason accepted shelter with the Owens’ family, finding work as a midwife and nurse, serving in a physician’s office on Main Street and even in the same county jail in which she’d taken refuge with 14 other enslaved people fighting for freedom. She braved a smallpox epidemic during the 1860s, risking her life to tend to the sick and earned a reputation as an excellent midwife, delivering hundreds of babies over her career. After ten years of hard work and frugal living, Mason spent $250 to become one of the first Black women to own property in Los Angeles. Running between Spring Street and what is now Broadway, Mason’s homestead occupied a part of Los Angeles with more gardens and vineyards than paved streets, a fitting place to gather her family, nurture their ambitions, and grow her own.

Mason leveraged her wealth as a property owner to buy more property, and continued her calling to help people. She gave room and board to the destitute and visited the imprisoned. Just as she built generational wealth, Mason invested in institutions to serve the community; she organized the first African American Church in Los Angeles, a traveler’s aid center and a primary school for young black people. Mason’s remarkable spirit was evidenced in the words she spoke to her granddaughter: “If you hold your hand closed, Gladys, nothing good can come in. The open hand is blessed, for it gives in abundance, even as it receives."

This story relies heavily on Dolores Hayden’s The Power of Place: Urban Landscapes as Public History, an excellent resource to learn more about how Mason and other underrepresented people helped shape Los Angeles.