STORY

The Hart Museum remains closed. Los Angeles County has approved a plan to transfer the William S. Hart Museum and Park from the County to the City of Santa Clarita.

The Hart Museum remains closed. Los Angeles County has approved a plan to transfer the William S. Hart Museum and Park from the County to the City of Santa Clarita.

In 1785, a Gabrieleno-Tongva woman named Toypurina led a revolt against the Spanish colonizers at Mission San Gabriel, cementing her legacy as a symbol of Indigenous resistance and fortitude.

For many people who went to elementary school in California, the mention of a California mission recalls memories of a mandatory fourth-grade diorama project. Luckily, when my time came to be assigned a mission to construct, I was given the one down the street from my house. The presence of this 250-year-old building that was built when California was ruled by the Spanish monarchy looms large in my daily life. It is the “Pride of the California Missions,” Mission San Gabriel Arcángel. This particular building was constructed by the coerced labor of Indigenous people for the purpose of economic, social, and spiritual conquest. This building has defined the identity of my hometown of San Gabriel, California, in the heart of the eponymous valley. Despite its status as a historical landmark, the full extent of the mission’s challenging history is often obscured in favor of spotlighting its redeeming qualities. Civically speaking, more attention has been spent focused on its generative, rather than destructive, history. It is this plurality of opposing narratives that inspired within me an ideological reckoning with the identity of my hometown.

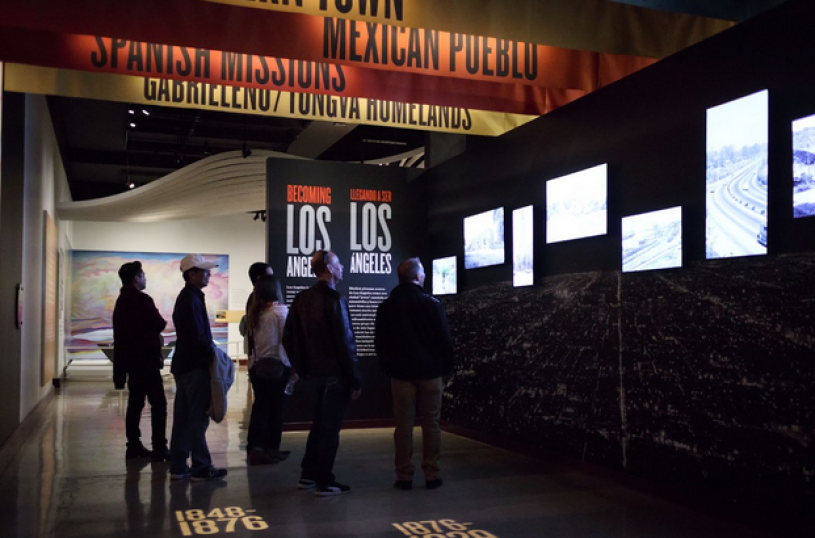

To those unfamiliar with the California missions, a label in the Museum’s Becoming Los Angeles exhibit directly summarizes:

California’s 21 missions, founded between 1769 and 1823, were critical to achieving Spain’s goals of increased revenue, strategic military outposts, expanded trade with Asia, and the creation of new Spanish subjects through the religious conversion of Native Americans.

I grew up near the Mission District in the City of San Gabriel, where imagery representing romantic notions of Spanish California is inescapable. Beneficent padres and welcoming Native Americans grace giant murals and sundry signage, but by far the most ubiquitous images are those of the mission’s famous bells. The mission bells can be seen on storefronts, sidewalk tiles, and atop street signs. For most of my life, these embellishments went largely unnoticed. I only began to consider the symbols that so thoroughly decorated my local upbringing after I noticed a particular artifact nestled in the Museum’s Becoming Los Angeles exhibit.

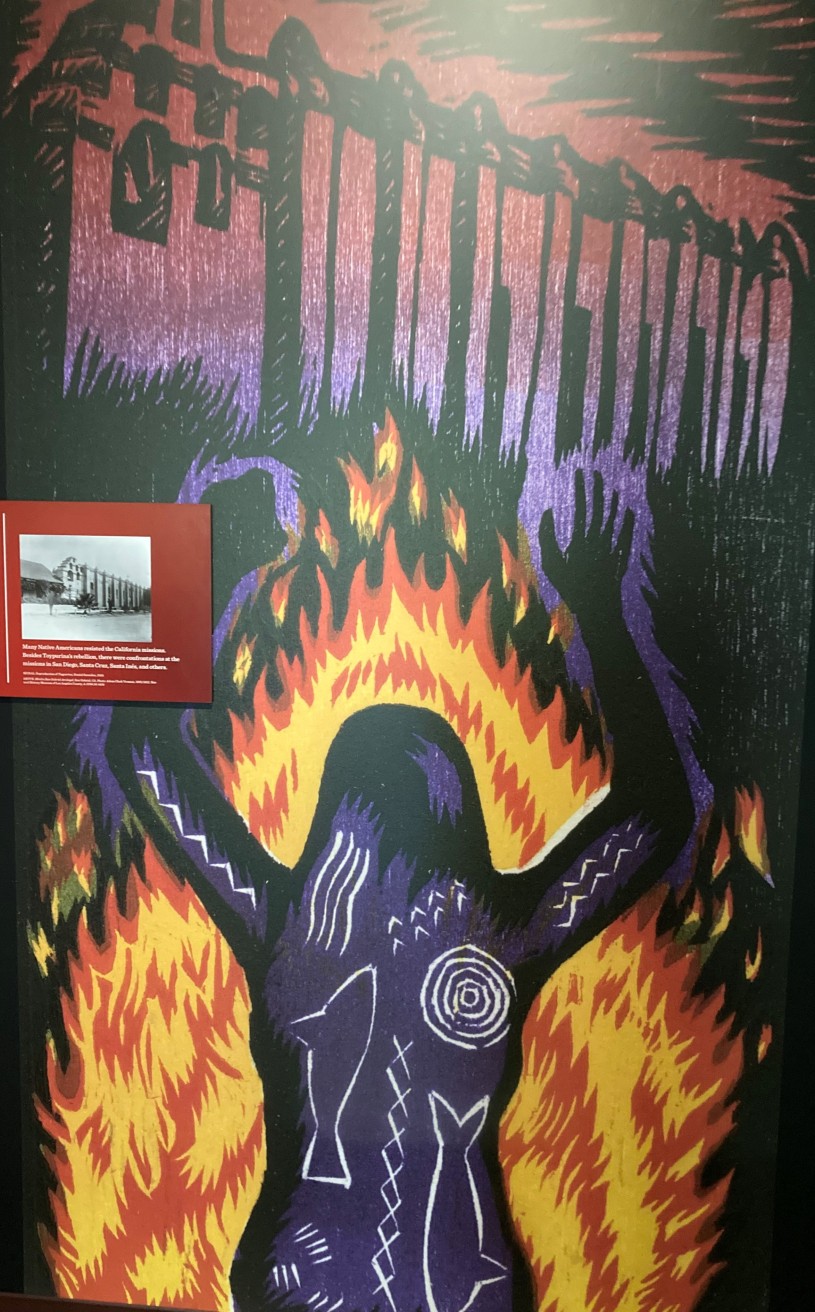

Beginning by chronicling the Indigenous inhabitants of Los Angeles and its outlying regions, the exhibit leads visitors along a chronologically curated pathway past cultural objects denoting the various claimants of Los Angeles–Spain, Mexico, and eventually, the United States. Framed paintings of the California missions hang on the wall amidst various objects signifying mission life. My attention, however, has been consistently drawn to a reproduction of a mural titled Toypurina, created by artist Daniel Gonzalez in 2014.

Toypurina was a Gabrieleno-Tongva woman famous for playing a critical part in an Indigenous uprising on Mission San Gabriel in 1785. Toypurina is depicted in the foreground of the mural, her silhouette tattooed with symbols of Indigenous life. Her hands are raised above her head in defiance and her body haloed by flames. Situated in the background and serving as the object of her fiery rage is the Mission San Gabriel Arcángel. Although the rebellion was thwarted by the Spanish, her story has gained mythical status in the San Gabriel Valley and beyond. However, the allure of this colorful mural had consistently diverted my attention away from an adjacent glass vitrine housing three seemingly innocuous items: a rosary, a single leather sandal, and a mission bell.

At first glance, the items in this case could easily be viewed as mere antiques, physical tokens of a bygone past. They were symbols of the rote and oversimplified history of the California missions that populated the pages of my elementary school history textbooks. I read the accompanying label. It stated:

The sound of this mission bell signaled the start of prayer, work, meals, and sleep. The Franciscan priest punished any Indigenous neofitos (converts) who strayed from the strict schedule. As one 18th century visitor described, “The men and women are collected by the sound of a bell…We observed with concern that the resemblance is so perfect [to a slave plantation] that we have seen both men and women in irons, and others in stocks. Lastly, the noise of the whip…”

This little bell had suddenly taken on a new meaning. It was no longer a simple relic of a history that I studied in the fourth grade, but instead revealed itself as a tool of enforcement and erasure, a cultural solvent.

I passed the mission on my way home that day, and the preponderance of the bell was unmissable. I looked at the famous façade of the mission’s bell tower differently for the first time in over 20 years. I thought back to the little bell in the Museum and to the quote of the 18th-century visitor to the mission, wondering where he stood when he made the observation that, “The men and women are collected by the sound of a bell…we have seen both men and women in irons…Lastly, the noise of the whip…”

To be specific, most of the imagery of bells inside the Mission District is of the mission’s six-bell “campanario”, or bell wall, which was constructed in 1812, after the original three-bell structure toppled in an earthquake. The bell in the Museum is simply labeled as “mission bell” and was purportedly used by the Spanish friars at Mission San Fernando. However, the original intent behind these instruments was the same during the period of Spanish colonization–to martial with military precision the physical labor and spiritual conversion of a subjected population.

It was then that I realized that the bell, the rosary, and the sandal were all displayed directly in front of the Toypurina mural. It is these material representations of the ruinous force of Spanish colonization that Toypurina rallies against, every day, in this small nook of the Museum.

In 2020, an act of arson destroyed the roof of Mission San Gabriel. This coincided with the 250th anniversary of the mission’s founding and generated renewed discussion around the controversies of the mission system. To gain a comprehensive understanding of these issues, I spoke with Chief Redblood Anthony Morales, the Tribal Chairperson and Chief of the Gabrielino-Tongva San Gabriel Band of Mission Indians.

I asked Chief Morales what the mission and its history means to him. He explained, “It was a forced transition for my people, bringing their lifestyle to an end…That’s what it means for me. [The Spanish colonizers] took our freedom, they took our land, and they took our lives. That’s exactly what they did.” However, after recounting the deleterious effects of the mission’s enterprise, he continued:

On the other side, we, as descendants of that ancestry, have to remember that at the San Gabriel Mission, the grounds are sacred to us because there are at least 6000 of our ancestors buried in and around those mission grounds. So for us it's a burial ground, it’s sacred ground, and if we don't have that closeness to the mission that means we will have been ignoring our ancestors who are buried there by the thousands and they would have died in vain.

What conclusions did I come to after this whirlwind of historical reckoning? Did I decide that people should feel guilty about having pride in this historical site? Absolutely not, as I am actually grateful for the mission. Living next to the mission has inspired my lifelong passion for history. I can even trace my decision to major in history and eventually to work at the Natural History Museum back to hours spent exploring the grounds as a child. Admittedly, the mission imagery has lost some of its sheen of civic pride, and now seems inextricably linked to the logistics of oppression. However, for many people including myself and members of my family, such reproaching analyses are tempered by fond memories of picnics on mission grounds or of solemn celebration in the adjoining Catholic church. What I do advocate for, however, is a more truthful and comprehensive understanding of the mission system beyond the grading rubric of a fourth-grade diorama project.

Every person’s relationship to the mission is different. It simultaneously stands as an example of Spanish Colonial architecture, a past hub of systematized cultural erasure, and a present-day gathering place home to solemn veneration. I argue that these elements can co-exist, so long as one does not subsume the others. To do so would lessen the significance of a place that has existed in a state of ideological flux for 250 years. The mission is an active exercise, clad in stone, brick, wood, and mortar, in thinking critically about the past and reconciling that with our present. As Chief Morales told me, “The truth needs to be told, don’t sugar coat it.”